- Courtesy

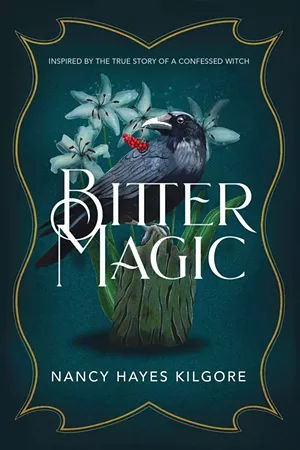

- Bitter Magic by Nancy Hayes Kilgore, Milford House Press, 278 pages. $19.95.

Judging by pop culture, sympathy for witches — or supposed witches — is currently at an all-time high. Whether we're talking about the spell casters of films Hocus Pocus 2 and The Craft: Legacy or the unjustly accused characters of Chris Bohjalian's best-selling Hour of the Witch, these are women who make the patriarchy uncomfortable, striking a chord with many viewers and readers.

It's not so easy, however, to celebrate a historical example of a woman who confessed to witchcraft — not just conceding under torture, as many suspected witches did, but volunteering an elaborate account of her dealings with the devil.

That woman is Scotland's Isobel Gowdie, whose case has fascinated and baffled commentators for centuries. Over six weeks in 1662, Gowdie made four confessions so detailed and colorful, combining local folklore with lurid accounts of demonic orgies, that some have suggested she was psychotic or suffering from ergot poisoning.

Gowdie's story is the core of Vermont author Nancy Hayes Kilgore's new novel, Bitter Magic. A former pastor and psychotherapist, as well as the author of two previous novels, Kilgore learned about Gowdie while researching her own Presbyterian Covenanter ancestors.

Harry Forbes, the minister who had Gowdie tried for witchcraft, was a hard-line Covenanter, a believer that every soul is predestined for heaven or hell. Gowdie was a "cunning woman," the traditional term for a purveyor of herbal remedies and lore. Kilgore suggests that her skills made her a threat to the minister's tenuous power over his rural congregation. With their eagerness to root out folk beliefs, the Covenanters didn't endear themselves to the peasants; the novel depicts an angry parishioner hurling a shoe at Forbes during his sermon.

In an author's note, Kilgore describes Forbes and Gowdie as "two different worldviews in a battle for authority" at a "turning point in history." But was Gowdie simply the innocent target of a zealot? Bitter Magic paints a more complicated picture — and a frequently enthralling one.

At the novel's center are two women. One is Isobel Gowdie, whose first-person voice flits in and out of the story. (The book alternates among several perspectives, with the others rendered in third person.) The ostensible protagonist, however, is the invented character of Margaret Hay, the 17-year-old daughter of the local laird.

Margaret is a character type common in young-adult fiction: a privileged, headstrong young woman who dreams of adventure and chafes against the restrictions of her era. Walking on the beach, she sees a pod of dolphins leaping, seemingly at Isobel's command, and becomes convinced that the peasant woman can control the natural world.

Isobel, who relishes her power as the hamlet's cunning woman, does nothing to dispel Margaret's impression. Gradually, she takes the girl under her wing as an apprentice, even as she nurses a grudge against Margaret's father, the dogmatic Covenanter John Hay. When Margaret's best friend is abducted by Highlanders, Isobel helps find her — and then offers an effective herbal remedy for the trauma resulting from her captivity and rape.

But Isobel's power has a dark side. When she summons a sandstorm to avenge herself on Forbes, the storm that appears ruins the crops and wounds her enemy. She calls on Catholic saints and fairies to assist her charms — but also sometimes on the devil.

Margaret finds herself wondering, "[W]ho or what was Isobel Gowdie? A battered wife, or a powerful cunning woman? A healer, or one capable of doing harm?"

Readers will also wonder. One of the book's greatest strengths is that Kilgore leaves open the central question of whether Isobel does, in fact, have supernatural powers. While Margaret's coming-of-age narrative is a bit programmatic, Isobel's chapters are fascinatingly elusive.

Kilgore's prose shines when she channels Isobel's voice, at once earthy and lyrical. She doesn't downplay the miseries of a 17th-century peasant woman's life: a peat fire-heated hut, emaciated children, and a husband whose brutishness is so routine that Isobel brushes off his assaults like a mere nuisance.

But Isobel seems to find a ready source of transcendence in her imagination. Lying in bed beside her hated husband, she envisions herself borne away to fairyland by a handsome spirit named William:

I sprang upon the horse calling, "Horse and hattock, ho! Ho and away!" And now I was aloft, and my body alive, every part, with the flight and the thrill and the speed. I was no longer hungry, and pain was unheard of, unknown, unimagined. My body was light — light as air. And now I was large, so great that I was part of everything, and everything a part of me. "Horse and hattock, ho!" I called again, and we flew through the night, over farmtown and field, over dunes and machair and mountains.

Whether this flight is real, a hallucination or wishful thinking, Isobel's visions have a powerful immediacy. And when they darken, as William transforms himself into the devil, they raise even more questions.

At one point, Kilgore suggests that witchcraft could have been a self-fulfilling prophecy — that the minister himself turned Isobel into a witch by persistently conflating semi-pagan folk traditions with satanism in his sermons. "Mister Harry [Forbes] called the fairies devils," Isobel says, "so William the Fairy Man took heed and became the devil."

But Isobel isn't particularly distressed by the supposed loss of her soul. Her pact with the devil is also a revolt against the ruling class, a reaction to John Hay's confiscation of the peasants' crops to make up for his own shortfall.

"It was sinful to traffic with the devil," Isobel reflects, "but what had the minister promised? No food for the starving, no magic to heal or strength to fight those who wronged us. Rewards only after death — and, in the meantime, the judgment of God." Rejecting the unhelpful abstractions of the only religion on offer, she chooses instead "to live, to thrive, both I and my family, in this life."

One might be reminded of the film The Witch, which ends with its young protagonist accepting the devil's offer: "Wouldst thou like to live deliciously?" Given the horrific hardships of her life as depicted throughout the film, her choice seems only sensible. Similarly, in Bitter Magic, Isobel turns to the devil (or imagines she does) only after realizing that promises of heaven won't feed her and her children.

Kilgore presents Isobel's case from a range of perspectives besides that of the smitten Margaret. Various chapters explore Forbes' point of view — he doesn't always practice what he preaches — and that of Katharine Collace, a real historical figure who serves in the novel as a counterpoint to Isobel. Saddled with a cruel husband, Katharine also struggles with her role in a Christian patriarchy. But she's an intellectual who draws strength from Covenanter theology even as she rejects antiquated practices, such as witch burning.

While Margaret's story is a little shopworn, Kilgore's juxtaposition of Isobel's story with Katharine's raises both fresh and enduring questions about the different forms of female power. The author complicates our modern tendency to assume that accused witches were merely victims of persecution and misunderstanding.

That may have been true as a general rule. But, much like the feminists who reclaimed the label of "witch" and cast hexes on Donald Trump during his presidency, Kilgore's Isobel is more interested in power than in politeness. The author says it best in one of her afterwords: "I think of Isobel's revenge rituals as, among other things, a pre-feminist fight for justice." Readers won't soon forget this witchy woman.

"bitter" - Google News

September 08, 2021 at 09:08PM

https://ift.tt/3yTLrCK

Book Review: 'Bitter Magic,' Nancy Hayes Kilgore - Seven Days

"bitter" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3bZFysT

https://ift.tt/2KSpWvj

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Book Review: 'Bitter Magic,' Nancy Hayes Kilgore - Seven Days"

Post a Comment